In our digitally interconnected world, ancient wisdom is more accessible than ever before. However, this accessibility comes with a significant risk: misinformation. Sensationalist claims often circulate online, creating confusion about foundational spiritual concepts. One such claim that has recently gained traction is the assertion that the Rigveda, the most ancient of the four Vedas, contains no mention of the Ātman (आत्मन्), the Self.

This idea is startling, as the concept of the Ātman is the very bedrock of Vedantic philosophy, which is understood to be the culmination of Vedic thought. Does this mean the core concept of the Self was a later development, absent from the foundational scripture of Sanatana Dharma? This article delves into the primary sources and traditional interpretive frameworks to investigate this claim and uncover the intricate truth woven into the fabric of the Vedas.

The Linguistic Trail: Finding ‘Ātman’ in Disguise

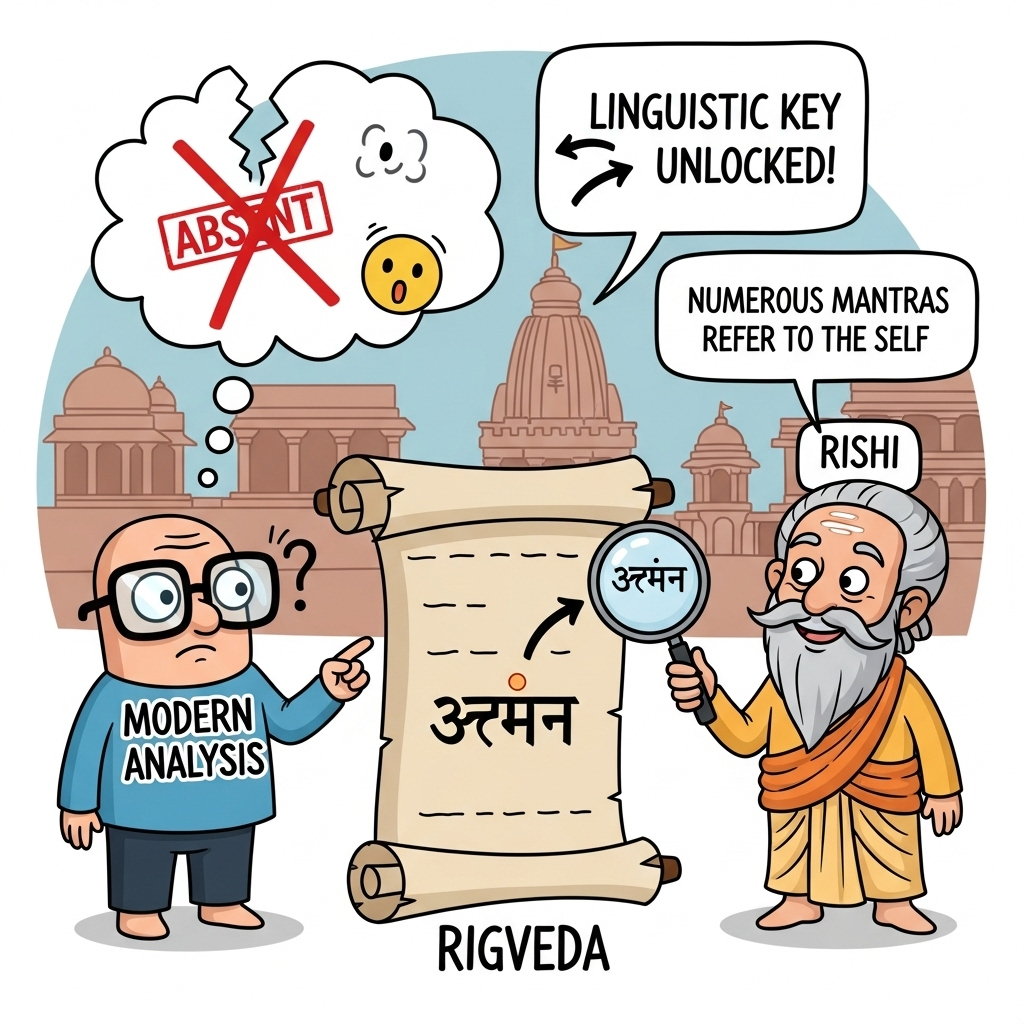

A simplistic keyword search for the word ‘Ātman’ in the Rigveda Samhita might indeed yield limited results, leading one to a premature and incorrect conclusion. However, the Vedic language is nuanced, and a lack of surface-level evidence does not signify absence. The key lies in understanding a subtle linguistic variation.

In the Rigveda Samhita, the concept of Ātman is frequently expressed using the word Tman (त्मन्). In Sanskrit grammar, it is common for the upasarga (prefix) ‘आ’ (ā) to be dropped in certain contexts. Therefore, the words Tman (त्मन्) and Tmanā (त्मना) are used synonymously with Ātman (आत्मन्) and Ātmanā (आत्मना).

Once this linguistic key is understood, one finds numerous mantras in the Rigveda that indeed refer to the Self using this form. The claim that the concept is absent is thus debunked on a purely linguistic basis. This highlights a critical flaw in modern, decontextualized analysis: a failure to engage with the grammatical and semantic subtleties of the Sanskrit language as it was used by the Rishis.

Understanding the Vedic Structure: Beyond the Hymns

To properly assess the presence of any philosophical concept in the Vedas, one must first understand that the Vedas are not a single, monolithic book. They are a vast corpus of knowledge, systematically organized into different sections, each with a specific purpose. Broadly, each Veda is composed of four parts:

- Samhitas: The core of the Veda, consisting of mantras and hymns. The Rigveda Samhita, for example, is primarily a collection of hymns (ṛks) dedicated to various Devatas (cosmic principles or deities) intended for recitation during Yajnas (fire rituals).

- Brahmanas: Prose texts that explain the intricate details, symbolism, and procedures of the rituals mentioned in the Samhitas.

- Aranyakas: Known as the “forest texts,” these form a bridge between the ritualistic Brahmanas and the philosophical Upanishads, often exploring the esoteric meanings behind the rituals.

- Upanishads: These form the concluding portion of the Vedas and are thus called Vedanta—the ‘end’ or ‘culmination’ of the Veda. This section moves from ritual to pure philosophy, focusing on metaphysical inquiry, the nature of reality (Brahman), and the nature of the Self (Ātman).

Therefore, while the Samhitas are focused on invoking cosmic forces, the deepest philosophical inquiries, including explicit and detailed discussions on the Ātman, are naturally found in the Upanishads. To search for a fully elaborated philosophical doctrine in the hymnody of the Samhita and ignore the Upanishad attached to that very Veda is a fundamental methodological error.

Examples from The Aitareya Upanishad of the Rigveda

The claim that the Rigveda does not discuss the Ātman collapses entirely when one turns to its own integral Upanishad: the Aitareya Upanishad. This Upanishad is not a separate text but is an inseparable part of the Aitareya Aranyaka of the Rigveda.

The very first sentence of the Aitareya Upanishad begins with the word in question:

आत्मा वा इदमेक एवाग्र आसीन्नान्यत्किञ्चन मिषत्।

(Aˉtmaˉvaˉidamekaevaˉgraaˉsiˉnnaˉnyatkin~canamiṣat)

This translates to: “In the beginning, this was the Self (Ātman) alone, one only; there was nothing else that winked.“

This single, powerful opening statement is irrefutable proof. The Rigveda, in its philosophical culmination, not only mentions the Ātman but places it at the absolute beginning of creation as the sole, primordial reality. The rest of the Upanishad elaborates on how this one Self created the entire cosmos, the worlds, the Purusha (Cosmic Consciousness), and within that, the concepts of Manas (mind) and Indriyas (senses). This is not a fleeting mention but a detailed, profound exposition of a well-realized metaphysical principle.

The Perils of Misinformation: A Case of Flawed Etymology

The same sources that make these erroneous claims often compound their error with misleading interpretations. For instance, one common mistranslation claims that Ātman literally means “that which transcends the mind.” This is a conceptual interpretation, not a formal etymology, and it is misleading.

The traditional Vyutpatti (etymological derivation) from ancillary Sanskrit texts like the Unadi Sutras provides a more grounded meaning. One definition is:

अतति निरन्तरं कर्मफलानि प्राप्नोति वा स आत्मा

(atatinirantaraṃkarmaphalaˉnipraˉpnotivaˉsaaˉtmaˉ)

This means: “That which continuously wanders (i.e., reincarnates) and obtains the fruits of its actions (karmaphala) is the Ātman.” Another meaning given is आत्मा शरीरन्तर्गतः (ātmā śarīrantargataḥ), meaning “that which rests inside the body.“

These classical definitions are consistent with the doctrines of karma and reincarnation found within the tradition, a stark contrast to the simplistic and unsubstantiated definitions often found online. This demonstrates the danger of relying on third-party sources that are not anchored in the Shastras.

The Authentic Approach: Reclaiming the Traditional Method of Study

The entire controversy stems from applying an alien, reductionist methodology to a holistic and deeply integrated system of knowledge. The traditional Indian Knowledge System (IKS) views the Vedas not as historical artifacts to be dissected chronologically but as a unified body of revealed wisdom.

The Western Indological theory that the four Vedas were composed in a linear sequence is not the traditional view. According to tradition, there was one Veda, which was later organized (vyasanam) into four distinct collections by Maharishi Krishna Dwaipayana, earning him the title Veda Vyasa (“the compiler/divider of the Vedas”). This division was done for the convenience of study and ritual performance. A Yajna requires priests expert in all four Vedas—the Hota (Rigveda), Adhvaryu (Yajurveda), Udgata (Samaveda), and Brahmana (Atharvaveda)—working in concert. This proves that the four Vedas are not separate books but interdependent parts of a single, unified corpus.

Furthermore, the Vedas were never meant to be read like modern textbooks. They are expressions experienced by Rishis in the highest states of consciousness, communicated in a “coded” language known as Paravani. Unlocking their meaning requires guidance from a Siddha Guru (a realized master) within a proper lineage (parampara).

This holistic approach is beautifully encapsulated in a famous verse from the Mahabharata:

इतिहासपुराणाभ्यां वेदं समुपबृंहयेत् |बिभेत्यल्पश्रुताद्वेदो मामयं प्रतरिष्यति ||

(itihaˉsapuraˉṇaˉbhyaˉṃ vedaṃ samupabṛṃhayet∣bibhetyalpasˊrutaˉdvedo maˉmayaṃ pratariṣyati∣∣)

This means: “One should elaborate upon the Veda with the help of the Itihasas (epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata) and the Puranas. The Veda fears a person of little learning, thinking, ‘This one will misinterpret me.’“

To truly understand the Vedas, one must engage with the entire ecosystem of texts, including the Vedangas (limbs of the Veda) and Upavedas (subsidiary Vedas). Knowledge is not meant to be acquired for intellectual aggrandizement, which leads to ego. It is a sacred pursuit to be approached with reverence—hence the tradition of adding ‘Sri’ as a prefix, as in Sri Rudram or Srimad Ramayana. The true test of Vedic knowledge is not what you can quote, but what it does to you. It should lead to humility, wisdom, and spiritual transformation.

Hence, the claim that the Rigveda lacks the concept of Ātman is demonstrably false. It is refuted by linguistic evidence within the Samhita itself, by the structural logic of the Vedic corpus, and most decisively, by the direct and profound teachings of the Rigveda’s own Aitareya Upanishad.

This issue serves as a valuable lesson. To seek authentic knowledge, we must move beyond facile internet searches and the pitfalls of secondary sources that lack scholastic rigor. The path to understanding these profound texts lies in returning to the primary sources, making a sincere effort to learn Sanskrit, and seeking the guidance of qualified teachers who uphold the traditional methods of study. Only then can we hope to drink from the true nectar of the Vedas and engage with their transformative wisdom as it was meant to be experienced.